Introduction

There remains some confusion by many in the lay world (to whom most Emergency Managers report) regarding “Operations Centres.” In the first place, “what exactly are they called?” Naming conventions for the “Centre” change from site to site and organization to organization. For example, there are Operations Centres, Command Centers, Incident Command Centres, Situation Centres, Emergency Operations Centres, War Rooms, and Command Posts.

In the second place, those who are designated as principals in organizational response and recovery plans are often heard asking: “What are these places? Are there major differences between each of these iterations? What’s their purpose? Who staffs them? What do they look like?”

Are the answers to these questions as varied as the nomenclature? Are confusion and head scratching about “Operations Centres” characteristics of disaster management?

This article offers a prescriptive definition and description in an attempt to allay some of the confusion surrounding Operations Centres, and further offers a provocation to thought as to the space, materiel, and administrative requirements typically associated with one.

Note: This article speaks to Operations Centres in the context of Incident Command.

What’s in a name

Not long ago, I was invited to speak on the topic of Disaster Management and was asked what I would name the presentation. I landed on the title: “Emergency, Disaster, Crisis, Calamity, or Bad Day?”

I mention this to make the point that, although the literature can be trusted to provide detailed differences between one term and the other, the reality is – the names people use to describe events are often interchangeable.

Let’s agree for the remainder of this article on the use of the term “Operations Centre” abbreviated as OpsCen.

Defining an OpsCen

An OpsCen contains the accommodations and communications necessary to direct disaster response and recovery operations. It is staffed by representatives from the functional sections of an organization’s incident management team, but its precise staff makeup is determined by the senior leader (Incident Commander) as dictated by the requirements of the situation.

Its primary functions include the provision of:

a. a physical link between corporate office and its affected sites/facilities, or

b. a physical link between management and staff involved in event response and recovery operations,

c. a real-time communication capability between the organization and other (external) responding agencies,

d. an effective and efficient mechanism to provide real-time information to the Incident Commander regarding any significant development,

e. an effective and efficient mechanism to maintain an inventory of organizational resources and to facilitate their deployment and commitment,

f. an effective and efficient means to acquire needed resources from the organizational supply chain, or from suppliers and/or other involved agencies/jurisdictions, and

g. timely and accurate information to higher authority, e.g., corporate HQ/board of directors in the private sector or municipal/county/state (provincial)/ federal officials in the public sector.

How much bigger than a breadbox is it?

The commonly held perception that an OpsCen is a single, albeit, large room accommodating all those with principal roles in disaster management, including the Incident Commander, must be dispelled!

Events requiring the use of an OpsCen are usually characteristic of an increased reliance on information. Decision-making under disaster circumstances poses challenges not normally experienced in day-to-day operations and will almost certainly be exacerbated by noise, confusion, and chaos.

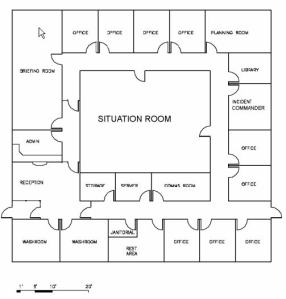

In an effort to impose order and structure where there may be little or none, an OpsCen provides a number of functionally specific areas. Figure 1 offers a sample and generalized sample of the Opscen.

Figure 1

The first of these, which I shall refer to as a Situation Room, is dedicated to the management of response and recovery operations, e.g., deployment and employment of personnel, requesting and releasing resources, ongoing monitoring of the situation, and providing up-to-date information to the Incident Commander. Figure 2 provides an example of an austere Situation Room configuration, while Figures 3 and 4 show more elaborate setups.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

The Situation Room is “activity central” and highly reliant on information collection, display, and distribution. It’s staffing is normally limited to those who are assigned roles and responsibilities regarding the minute-byminute, hour-by-hour management of operations and access to it is strictly controlled. The exact makeup of the staff assigned to the Situation Room is typically situation-dependant, but would intuitively include a combination of Command Staff, Operations, Logistics, and other principals responsible for the management of event activities.

The Situation Room is not a gathering place for curious onlookers. It is not a location intended as a space from which to conduct media or other briefings, nor is it a location conducive to strategic, planning, logistic, administration or finance meetings. Rather, it is an information hub for the Incident Commander’s – a decision-making assistance tool. It is a location the Incident Commander may visit or occupy from time to time to collect real-time situation reports and updates.

A Planning Room is dedicated to those responsible for fully assessing the situation, determining the length of an operational period, forecasting the requirements of the next operational period and beyond, revising existing action plans or crafting entirely new action plans as the situation warrants and/or as the Incident Commander may direct. The Planning Room is the location of the organization’s brain-trust and the province of the Planning Chief. Dependant on availability of space and resources, the Planning Room may resemble a typical conference room as shown at Figure 5.

Figure 5

When planners are somewhat removed from the minute-by-minute, hour=by-hour din, they are more easily able to step back from the action, collate and analyze the situational information, and make sounder recommendations to the decision-making authority.

Not unlike the Situation Room, the Planning Room is also heavily reliant on information collection and display. Its access is restricted and the Incident Commander visits from time to time to receive situation forecasts, courses open, and action recommendations.

A Briefing Room is provided for the use of the Incident Commander or the organization’s Public Information Officer to conduct media/public information briefings. Those from external agencies, including the media, who request information must be suitably accommodated without interfering or interrupting the response and/or recovery operations being conducted throughout the OpsCen. See Figure 6.

Figure 6

A Communications Room is a location from which alternate communication means may be provided to the OpsCen. It could allow, for example, the installation and operation of an Amateur Radio Station (example at Figure 7) staffed by ARES volunteers.

Figure 7

A separate and secure Server Room accommodates the requisite number of file servers and a workspace for a programmer/maintainer.

Paper copies of Disaster Management Plans, Disaster Management documentation, periodicals, books, brochures, pamphlets, newsletters, and information sheets published by various other agencies and jurisdictions should be at hand. A Library serves as a resource centre for mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery literature, research activity, and educational material including training aids and lesson plans.

An OpsCen includes offices. While it is not the intent of an OpsCen to necessarily provide office space for the organization’s entire staff, the principal actors in the organization’s incident management structure certainly require adequate accommodation. The Incident Commander, for example, should have an office appropriate to conduct regular meetings with command staff and section chiefs. Likewise, Command Staff and each Section Chief may be provided an office from which to work (when not busy in the situation room) and from which Section Chiefs may conduct meetings with their individual division heads.

There should also be an area designated as a Labour Pool and Volunteer Services Coordination Room. Those not engaged in continuity of operations or disaster response and recovery activities are centrally registered for assignment to any one of the Incident Management System’s sections through the Planning Section. Dependant on space and resource availability, a Labour Pool and Volunteer Services Coordination Room may be configured as Figure 8.

Figure 8

A Rest Area for those participating in protracted operations is necessary. However, the Rest Area is not a location where participating personnel can microwave food or purchase vending machine snacks or drinks, sit and eat. Rather it is a quiet, comfortable, softly lit area where OpsCen staff may take a few moments away from the high intensity of disaster operations. There ought to be as little distractions in this area as possible. An example visualization of a Rest Area is at Figure 9.

Figure 9

A Nutritional Area is available where OpsCen staff may store and cook food, eat and drink.

The expected number of staff/visitors involved in response and recovery activity at an OpsCen during a disaster event determines the allocation of adequate washrooms. The 24-hour, 7-day/week nature of OpsCen duties may also warrant the provision of shower facilities for shift workers or workers that are sheltered in place.

An Administration Area provides space for telephone and in-person reception, mail sorting, PC and facsimile use, secure file storage, and photocopier operation.

Finally, the quantity and frequency of meetings held with external agencies/organizations dictate a requirement for a Reception Area that, at a minimum, allows seating and coat storage. (Administration and Reception Areas at Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10

Figure 11

As can plainly be seen from the above, an OpsCen comprises many component parts. While some organization office suites may satisfy an OpsCen’s space requirements in full, others may not. What’s important is to understand the specific characteristics of an OpsCen and, as much as practicable, to designate appropriate space as necessary.

What else is required?

Although space designations go a long way toward implementing an OpsCen, without the tools enabling functionality in each dedicated room — an OpsCen may as well be a series of neatly named storage areas.

An OpsCen needs to be functional and its functionality is only achieved by providing for the requirements of power protection, telecommunications (telephone set and line, LAN drop, or wireless technology alternatives), equipment and materiel, audio-visual support, environmental controls (including heating, venting, air conditioning, and lighting), individual workspace, privacy and sound abatement, etc.

More?

In addition to space and functionality requirements, other administrative considerations are important in understanding the full breadth of an OpsCen. These include:

Location. An Operation Centre permits ready access by internal staff, local officials, and other authorized visitors in times of disaster. Its location is such that the risk of being cut off by reason of floodwaters, dangerous goods accidents, rail derailments, or major air disasters is minimized.

Security. The confidentiality of information and the sensitivity of disaster response and recovery activities dictate strict access control and monitoring.

Parking.

• The number of parking stalls provided is determined by accounting for the OpsCen’s maximum staff compliment as well as the upper limit of attending participants at meetings.

• Local historical winter weather conditions dictates whether or not parking stalls are equipped with electrical outlets, and

• The 24-hour, 7-day/week nature of OpsCen duties dictates a need for adequate nighttime illumination.

Conclusion

The above paragraphs prescribing and pictures illustrating an OpsCen are intended to help provide a better understanding of the broader scope of OpsCens and goes to answering the questions: “What they are? What their purpose is? Who staffs them? What they look like?”

Having discarded the one-room-general-purpose-all-in-one perception and looking for the organization’s Opscen now may lead to the discovery that most of the space, materiel, and administration considerations defining an OpsCen are, in some cases, already in place but have never formally been confirmed, labeled, or prepared accordingly. In other cases, the discovery will reveal gaps and deficiencies between actual space and resources available and the prescriptive suggestions of this article.

In any case, events calling an OpsCen into play invariably pose extraordinary decision-making challenges and the activity level associated with disaster operations may be exacerbated by noise, confusion, and chaos. Prescribing the OpsCen is useful in imposing order and structure in the management of disaster operations where there may be little or none.

Prepared by: Guy Corriveau, B.Sc., MPA, CEM ®